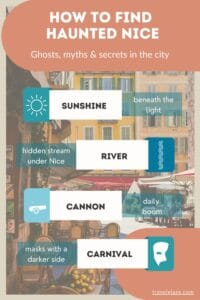

✨ Beneath the Sunshine

Golden light, pastel façades, the sparkle of the Mediterranean — Nice seems made for postcards. But beneath the sun-drenched surface hides another city, one built on shadows, whispers, and old legends.

There’s a river that still flows unseen under the streets, a cannon that startles the city awake every noon, and tunnels that may still keep secrets from centuries past. Even the carnival masks and the villas of artists carry stories that blur the line between memory and myth.

Pin this for later

This is Nice as you rarely see it: not glamorous, but haunted.

want to explore the haunted side of Nice step by step? Jump straight to the stories here:

☀️ Beneath the Sunshine

🌊 The River Beneath the City

💥 The Noon Cannon

🎭 Carnival Spirits

🖼️ Ghosts of Artists and Writers

🌊 The River Beneath the City

Nice looks sunny and solid, but beneath the streets another city flows. The Paillon River once cut through Nice, carrying fresh water from the mountains into the sea. In the 19th century, parts of it were covered to make space for boulevards and squares. Today, the river still runs — but hidden, unseen, and sometimes forgotten.

Local legends say the river is restless. Some claim that on stormy nights you can hear its roar under Place Masséna, as if the water is reminding the city that it never disappeared. Others tell stories of floods and drowned souls, ghosts that still wander the Old Town when the underground current rises.

💡 Fun fact: The Promenade du Paillon, the city park built above the river’s course, takes its name directly from this hidden stream. Families now stroll, children play in fountains, and few realize there’s a real river flowing just a few meters below.

📍 Where to see it:

Walk along Promenade du Paillon (between Place Masséna and the sea).

👉 Practical detail: The Paillon occasionally causes engineering challenges. When heavy rains fall in the hills, the underground river still swells — a reminder that even in a city built for sunshine, nature runs just beneath.

💥 The Noon Cannon

Every day at exactly 12:00 PM, a thunderous boom rolls across Nice. Locals call it lou canoun de Miejour — the midday cannon — and for over 150 years it has marked the city’s rhythm.

Fact vs. Legend

Most visitors hear a charming tale: Sir Thomas Coventry, a distracted nobleman, fired the cannon to call his wife home for lunch. It’s a great story — but mostly folklore.

In reality, Coventry wasn’t a nobleman but a British jurist with a passion for precise timekeeping. Around 1861–1863, he financed a system to synchronize the city’s clocks. A red time-ball was lowered from the roof of the Hôtel Chauvain to signal noon. The cannon master on Castle Hill then fired the shot, giving the whole city a reliable time marker.

What Really Happened

The practice became so popular that after Coventry left and later passed away, the city council formalized the custom. What began as a private initiative turned into a civic tradition.

💡 Fun fact: The cannon was fired with real gunpowder until 1992. Today, an electronic detonation keeps the tradition alive — just as loud, but safer.

📍 Where to hear it:

The boom can be heard across central Nice. The cannon itself is located on Castle Hill (Colline du Château).

👉 Practical detail: Don’t be startled if your lunch glass rattles on a terrace at exactly noon — it’s Nice keeping time the old-fashioned way.

🎭 Carnival Spirits

For most visitors, Carnaval de Nice is a spectacle of color and joy — floats, music, and showers of flowers. But behind the masks lies a festival with centuries of history, and with it, a few darker tales.

From Celebration to Fire

Since the Middle Ages, Nice has celebrated carnival before the solemn days of Lent. The highlight comes at the end, when the giant figure of the “Carnival King” is burned in flames by the sea. Some say this fiery farewell sends the spirit of the festival into the night — others whisper it also awakens older ghosts, drawn to the chaos of masks and fire.

The Masks That Linger

Legends claim that not all carnival masks are harmless. A few are said to “remember” the wearers from centuries past, carrying their spirit from parade to parade.

Along the Promenade des Anglais, where the Carnival King is burned.

At the Bataille de Fleurs, where flowers fly through the air.

🖼️ Ghosts of Artists and Writers

Nice has always attracted dreamers. Painters, poets, and novelists came here for the light, the sea, and the promise of inspiration. But in the city’s quieter corners, people still speak of these artists as if they never really left.

Whispers of the Studios

Henri Matisse spent his final years in Nice, painting in a sunlit apartment near the sea. Locals say that on certain afternoons, the light in his former studio still glows in an uncanny way, as if his brush had only just left the canvas. Marc Chagall, too, found inspiration here; his biblical scenes are now housed in the Musée Marc Chagall, but some visitors insist the building itself carries his presence.

Writers by the Riviera

Nice wasn’t only for painters. F. Scott Fitzgerald and other writers of the Jazz Age walked its promenades, capturing Riviera decadence in their stories. Some say you can still “hear” their voices in the grand hotels they once haunted — echoes of cocktail glasses and whispered lines from unfinished novels.

💡 Fun fact: The Musée Matisse and Musée Marc Chagall are unique in Europe: two entire museums dedicated to artists who lived and worked in Nice. Few cities can claim such a legacy.

📍 Where to feel it:

Musée Matisse (164, avenue des Arènes de Cimiez)

Musée Marc Chagall (36, avenue Dr Ménard)

Stroll the Promenade des Anglais and peek into the historic hotels where Jazz Age writers stayed.

👉 Practical detail: Both museums are closed on Tuesdays. If you plan a culture day in Nice, check opening times in advance — they don’t always align with other local museums.

🌟 Final Thoughts

Nice may shine in sunlight, but it also thrives on shadows. The hidden river, the booming cannon, the sealed tunnels, the carnival masks, and the lingering artists — each story adds another layer to the city. None of these tales are proven fact; they live somewhere between history and imagination, repeated so often that they’ve become part of local identity.

Some visitors leave Nice with postcards of the Promenade. Others leave with a different memory: a draft of cold air in an old cellar, an echo in the empty streets at midnight, or the sudden feeling that someone just walked beside them.

✨ Mini-legend: In Vieux Nice, locals sometimes whisper of a faceless figure that appears during carnival nights, slipping through the crowd and vanishing before the parade ends. Nobody can say if it’s real — but the story returns, year after year.

Whether you believe the legends or not, they make wandering Nice a little richer, and perhaps a little stranger.

Which of these haunted legends of Nice intrigued you most? Have you ever experienced something in the city that felt a little… unexplained? Share your story in the comments — I’d love to hear your version of haunted Nice. 👇